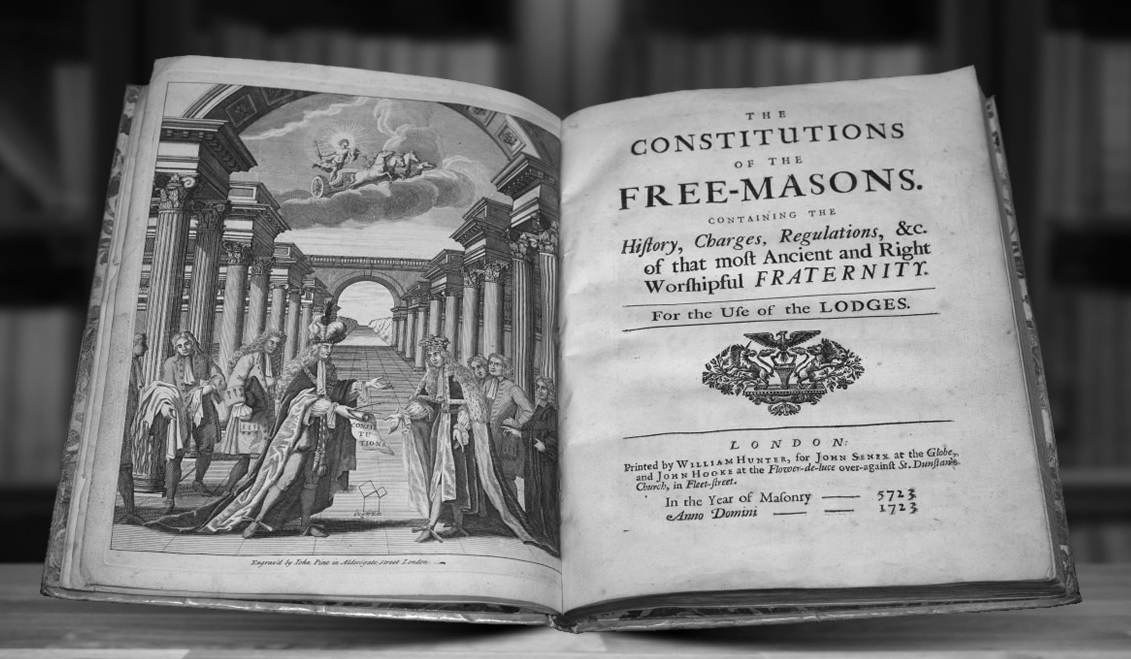

- The 1723 Constitutions

- The Context

- The Protagonists

- Britain, Ireland & Empire

- America

- Europe

- Events & Publications

- Contact Us

Mirroring the approach adopted in the Old Charges, James Anderson’s account of freemasonry’s development ‘from the Beginning of the World’ is designed to set a literary context for the Craft. By positioning freemasonry as an ancient institution dating back to Adam, in Anderson’s words ‘our first parent’, the narrative gives the new Grand Lodge of England legitimacy and status, and offers an aura and attraction that a more recently formed organisation would have found more difficult to achieve.

Bob Cooper makes this point in his 2002 paper in AQC 115:

None of the ‘Traditional Histories’ of any of the branches of Freemasonry are, or were, intended to be taken literally. Our forebears in all the Orders manufactured suitable ‘pasts’ for allegorical purposes. They did so with romantic notions at heart but understood that these histories were not literal truth.

Tony Baker’s Paper, ‘Lionel Vibert and the 1723 Constitutions’ explores this similarly.

Freemasonry’s perceived longevity conferred kudos in a tradition-based society but few, if any, at the time would have taken the history as a literal and truthful record of events. It was then and should now be viewed as falling within a schematic of literary hyperbole. Indeed, a similar approach was followed in the 1750s when the ‘The Grand Lodge of England according to the Old Institutions’, a new and rival grand lodge, adopted the name ‘Antients’ and Laurence Dermott, their Grand Secretary, disparaged the Grand Lodge of England as ‘Moderns’ to assert the greater credibility of the younger of the two bodies.

Several historians have assigned to Anderson sole authorship of the 1723 Constitutions. That this is improbable is discussed in ‘The Protagonists‘, which puts forward the argument that Anderson was more probably a ‘hired pen’ working under the principal direction of Jean Theophilus Desaguliers and the publishers, Senex and Hooke. And although Anderson’s traditional history dominates the text in that it is quantitively the largest component of the 1723 Constitutions, it is significantly less important when compared with the Charges and General Regulations.

A number of commentators including Brendan Kyne and Mike Kearsley have suggested that although Freemasonry adopted 4000 BCE as its nominal year of inception, this was not linked to Archbishop Ussher (1581-1656) and his dating of creation to 23 October 4004 BCE. Kyne and Kearsley suggest instead that the date may be associated with Sir Isaac Newton’s historical calculations. Newton, although not a Freemason, influenced many of the founders of the Grand Lodge of England (then known as the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster). If so, the letters ‘AL’ on Masonic membership certificates do not stand for Anno Lucis, the Year of Light, but rather Anno Latomorum, the Year of Masonry, as printed on the cover page of the 1723 Constitutions.